Knowles, Taylor & Knowles,, East Liverpool, Ohio

Knowles, Tayor & Knowles

A desire to prove that American potters could create a product that surpassed, in quality and beauty, that of their European competitors, was probably the impetus behind the creation of Lotus Ware. In 1887, Knowles, Taylor and Knowles added a five story China Works plant and began producing an art china that they called Belleek. At this time, K. T. & K. was the world’s largest pottery. Joshua Poole, from Stoke-on-Trent in the Staffordshire pottery district of England was hired to perfect the clay body for this new product. He formerly served as manager for the famous Belleek Pottery Works Company in Belleek, County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. (East Liverpool Review, 1928).

Unless noted, all the Lotus Ware depicted in this Docent Chat is from the collection of Marc and Cindy Hoffrichter.

Lotus Ware

Knowles, Taylor & Knowles

This exhibit, Crockery City Teapots, has a gallery devoted to Lotus Ware teapots. These teapots are probably the most valuable, in a monetary sense, of all the teapots in the exhibit. This is simply because they are Lotus Ware, a bone china, art pottery made by Knowles, Taylor and Knowles of East Liverpool at the turn of the nineteenth century. These teapots are over 120 years old; they are rare and they are the apex of East Liverpool’s pottery production.

While many Lotus Ware pieces were strictly decorative, such as vases, ewers, and rose bowls, elegant food service items were produced as well. These included delicate tea sets, demitasse cups and saucers, salts, pitchers and even a punch bowl. No dinnerware was produced.

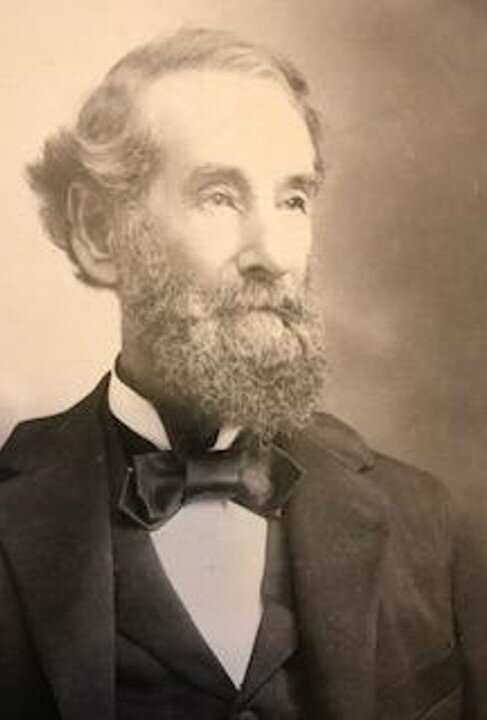

Joshua Poole

The Museum of Ceramics owns many of Poole’s diaries containing clay recipes (left). Poole remained at Knowles, Taylor and Knowles even after Belleek and Lotus Ware were discontinued. A letter in the possession of MoC confirms that, in 1898, he became general manager at a salary of $3,000. That is equivalent to $85,000 in today’s money. After 18 years of service at K. T. & K, he became general manager at Homer Laughlin China Company for an additional 16 years. Following that, he was Vice President of Edwin M. Knowles pottery. (Joshua Poole, 1928)

Very few pieces of K. T. & K.’s Belleek exist today. One small cream pitcher, which does not bear a trademark, is part of the Museum of Ceramics collection. The only known marked pieces are depicted in Alice Frelinghuysen’s book American Porcelain. It was the similarity of the creamer to these marked pieces that enabled museum staff to attribute the creamer as Belleek.

On November 18, 1889. a gas leak near the packing room of the China Works resulted in a fire that put an end to the production of Belleek. It was a devastating financial loss for K. T. & K. and several hundred employees were out of work. The company immediately made plans to rebuild. An interesting side note is that this disastrous fire was a turning point in the city’s fire prevention practices. The city ordered a Silsby water pumping fire engine in 1890 and added employees to the force (Council Ledger, 1890). The new K. T. & K. plant would be the first pottery to have a sprinkler system (Cox, 1938, Gates, 1984).

K. T. & K. China Works the day after the fire (1889) Decorators from the plant found a pane of glass and, in gold, wrote these words on it: “Of the 9,400 lights of glass in the China Works, this is the only one found whole after the fire, Nov. 18th, 1889. K. T.& K.”

The glass pane is in the collection of the Museum of Ceramics.

This is the only piece of Knowles, Taylor and Knowles Belleek in the collection of the Museum of Ceramics.

In the new plant, Joshua Poole set out to create a superior bone china. As implied, bone china contains animal bone. Lucille Cox, journalist and local historian, speaking to 175 ladies of the DAR at the Traveler’s Hotel in 1940, explained the process this way: “to make lotus ware, (bones) were hauled from the slaughterhouses along Tanyard run, just north of East Liverpool. Great wagon loads of bones were brought to the factory and dumped into large vats where they were boiled until every particle of meat dropped away. Then the bones were dried, placed in kilns and burned to a powdery ash. Fortunately, the odor defies description.” (Lotus Ware, 1940)

Bone ash made for a stronger clay that could then be thinner for the elegant pieces. Lotus Ware also had a special glaze that has been described by many as “velvety.” Another unusual trait is that some pieces were made of dyed clay. The clay bodies may be pale green (celadon), dark green, or dark blue.

This rose jar is an example of the elaborate decorating that was often applied to Lotus Ware. Lotus Ware was also sold in an undecorated, pure white form so that ladies could do their own “china painting,” a popular pastime in the 1900s.

Henry Schmidt, a German born ceramic decorator known as a “fancy” worker, was recruited to decorate the ware. Schmidt had trained in Germany’s Meissen pottery and was highly skilled. He liked to work in complete privacy and stories abound of his difficult temperament. William Blake was hired as something of an intermediary. He wrote in a letter: “I was selected as Mr. Schmidt’s assistant by Ben Harker, foreman of the clay shop, for two specific reasons—one to help Mr. Schmidt who spoke only German to acquire a quick working knowledge of English and the other was so that if he should become ill or suddenly decide to leave, the firm would have someone to fall back upon to carry out the work. I kept this position for several years.” (Blake obit). Blake also explained the decorating processes that Schmidt used. He would make small leaves and petals in molds and apply them to the work by hand. A cornucopia tool, similar to an icing decorating tube was used to apply the filigree. Other pieces were hand painted.

Ionian (or Savonian) vase. For more info on this piece, click here. Museum of Ceramics collection.

Fortunately for collectors, Lotus Ware almost always bears a trademark. Exact dating is difficult, as even the dates of production are uncertain. Secondary sources cite 1891 (Gates, Ormerod), 1892 (Cox, Huston), and even 1894 (Kearns). In recent years, an Akron Beacon Journal article erroneously put the start date as 1872! The East Liverpool Review reported, albeit in 1901, that “In 1893, they began the manufacture of a fine are [sic] porcelain of Chinese white body and velvety glaze, which they called “Lotus” ware.” It is a fact that Lotus Ware won top prizes at the Chicago Columbian Exhibition which was held between May and October of 1893. It appeared in some store advertisements as early as March of 1893 and the Crosser-Ogilvie Company was selling it at the end of the year from a display that showcased “small and fancy articles suitable for Christmas presents.” It is fairly safe to assume that production began in 1892.

While Lotus Ware won top awards, was well-received and is still, to this day, highly prized, pottery competitors across the pond weren’t as enthralled with the ware’s debut. An article in London’s The Pottery Gazette, critiqued the entries in the Chicago Exposition and described Lotus Ware as such: “Knowles, Taylor, and Knowles Company, of East Liverpool, Ohio, who manufacture a good white porcelain which they term (for what reason I am unable to conjecture) “Lotus ware.” This ware is of good paste and is fairly well finished. The composition appears to be English lines and to contain bone. …but the Knowles glaze leaves much to be desired—it’s either excessively hard or greatly under-fired. The surface presents the well-known “pig skin” appearance, and in many places tears or lumps together.” The author goes on to mention its “lack of originality” and “crude form.” Despite the unkind review, the author concludes by saying if the glaze is remedied, Lotus Ware could go on to “rival our best English wares.” One wonders if the negativity is simply envy or fear of a rising rival. The author gets one final jab in by protesting K. T. & K’s use of English appearing trademarks by saying that American potters “will never make a name by slavish imitation.” (Chicago, 1893)

The end date of production is also unclear. It is widely believed that production ended around 1896 or 1897. However, in 1905, an entry in Glass & Pottery World, stated, “Knowles, Taylor, and Knowles are again making their fine range of Lotus Ware in bone china.” (Practical, 1905). Hodson’s Drug Store, 1905, advertised “last of the Lotus Ware made by KT&K on sale” (The East Liverpool Review, 1905). Perhaps it is just best to say that Lotus Ware was produced for less than ten years.

Considering the short production run, it rather amazing how many pieces of Lotus Ware still exist. The survival of the ware is probably due, at least in part, to the fact that this elegant decorative ware was mantel worthy and not for use by children. The Museum of Ceramics has the largest publicly displayed collection of over 200 pieces. Several private collections exceed this number. There was a time when finding Lotus Ware to purchase was a challenge, but the Internet has made it widely available. Pieces are regularly available now on eBay and other online auction sites.

The story of Lotus Ware could not be told without a word about Isaac Knowles, the founder of Knowles, Taylor and Knowles. According to those who knew him, Isaac was a fascinating man. He had eight children, perfected the shaft driven jigger, loved botany and local history, despised an untruth and was a good conversationalist.

His first brush with the clay industry came in 1840 when he delivered and sold ware out of a wagon for James Bennett, East Liverpool’s first commercial potter. He worked as a cabinet maker and carpenter until 1850 when he partnered with Isaac Harvey in a single kiln pottery. They were best known for their canning jars and even created a self-sealing jar. By 1870, Harvey had left the trade and Isaac brought his son, Homer Knowles, and son-in-law, John Taylor, into the firm to create Knowles, Taylor and Knowles. By 1891, K. T. & K. was incorporated with 1,000,000 dollars, boasted 29 kilns, and 700 employees and was the largest pottery in the world.

Isaac wasn’t content with producing just tableware but wanted to create a line of artware that would rival anything produced abroad. It was under his leadership that Poole and Schmidt were hired to create Belleek and Lotus Ware. It is said that when they showed Isaac a newly designed vase that looked like a blooming flower, he commented that it reminded him of a lotus blossom and the ware was thus christened Lotus Ware.

Lotus Ware was made to be decorative. Beauty for beauty’s sake. It may seem that the Lotus tea sets were an exception because they also play a functional role. A close look at any of the teapots in the Lotus Ware gallery however, will support the theory that they were primarily for adornment. They certainly were not for everyday use. Perhaps the tiny teapots with their lavish decor were treasured and used only for “company.” And perhaps because of this, a number of them still exist today. Be sure to check out the Lotus Ware Gallery to see more of these lovely sets.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barber, Edwin A. “Marks on American Pottery and Porcelain.” China, Glass, and Pottery Review Reprint in The East Liverpool Review (January 11. 1901)

“Chicago Exposition and American Potters.” The Potters Gazette (August 1, 1893) 90.

Council Ledger (1884 – 1890) 168.

Crosser-Ogivie. (ad) The Evening News Review, (December 11, 1893), 4.

“Practical Potting World.” Glass & Pottery World 1905.

Cox, Lucille. “This is the Colorful Story of Lotus Ware.” The East Liverpool Review (June 16, 1938): 5.. American Porcelain: 1770 - 1920

Frelinghuysen, Alice Cooney American Porcelain: 1770 - 1920 (New York, The Museum of Art, 1989) 213.

Gates, William C. and Dana E. Ormerod. The East Liverpool, Ohio, Pottery District: Identification of Manufacturers and Marks (Ann Arbor, The Society for Historical Archaeology, 1982), 99 – 127.

“Joshua Poole, Clay Broker, Dies in Penn Avenue Home.” The East Liverpool Review (March 26, 1928) 1.

Kearns, Timothy J. American Bone China: With Price Guide (Atglen, PA, Schiffer Books 1994)

“Lotus Ware Seen as a Symbol for American Women to Encourage U. S. Potters to New Achievements.” The East Liverpool Review (October 26, 1940): 8.

Tarter, Jabe. “Host Pottery Show in East Liverpool.” Akron Beacon Journal (April 26, 1970): E12.

Gates, William C. and Dana E. Ormerod. The East Liverpool, Ohio, Pottery District: Identification of Manufacturers and Marks (Ann Arbor, The Society for Historical Archaeology, 1982): 99 – 127.

Gates, William C. The City of Hills and Kilns: Life and Work in East Liverpool, Ohio. (East Liverpool, East Liverpool Historical Society, 1984): 113.